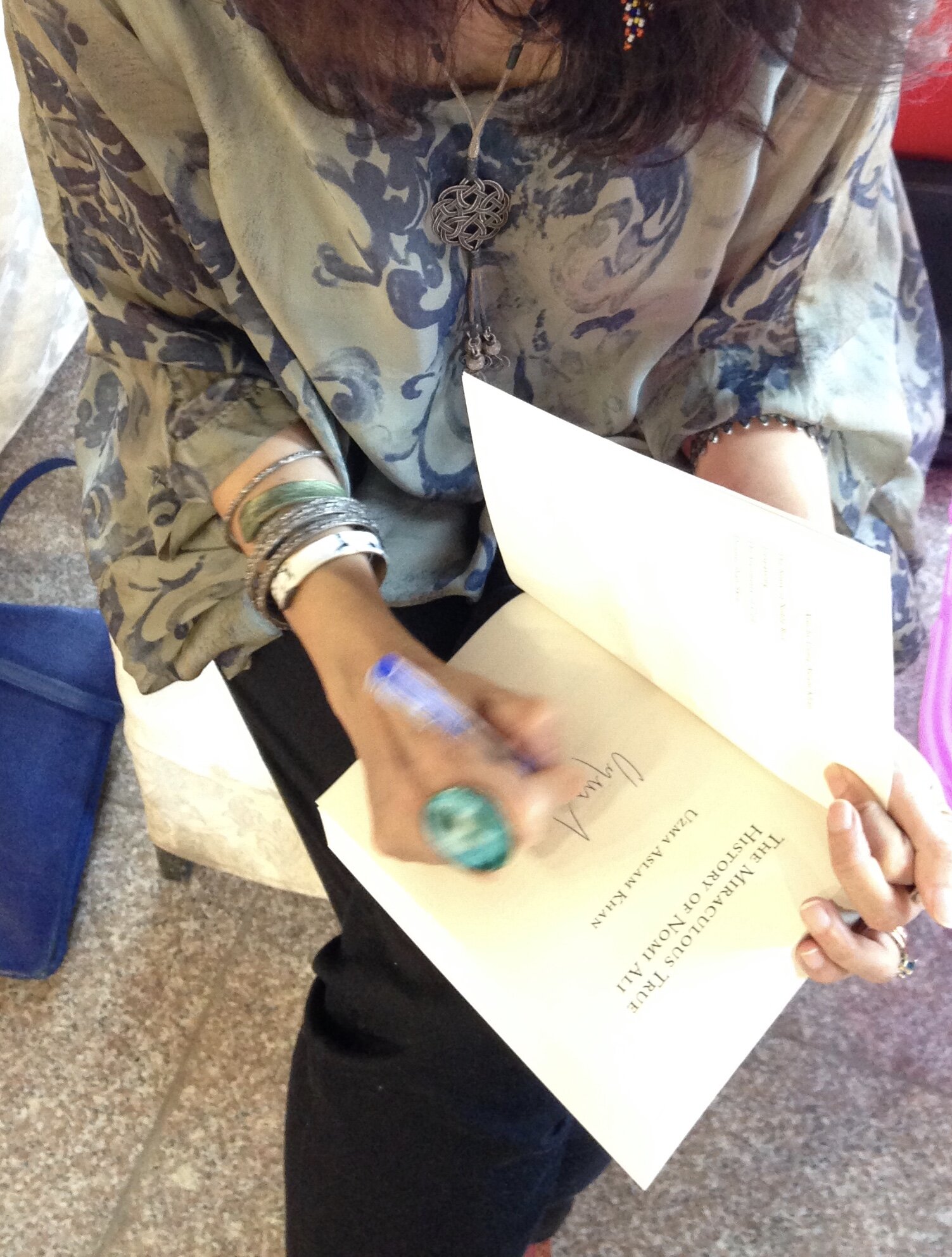

THE MIRACULOUS TRUE HISTORY OF NOMI ALI

—Interview Highlights

To me, the tenderness with which you write is a kind of intervention of knowing that is in opposition to the colonial one. For instance, the roles that surveillance and record-keeping play in the brutalities of the imperial project, versus the “knowing” of the Mayakangne, Kwalakangne, and Dare winds. There is the intimate knowing between Priya, the chicken, and Nomi, the human. The third-person omniscient narration suggests, again, a different kind of knowing. How do you think about the memories and interiors of others within this much larger context of layered surveillance?

I love what you say about “interventions of knowing.” It reminds me of Edward Said on knowledge: “Facts get their importance from interpretation [which] depend[s] on who the interpreter is, who he or she is addressing, what his or her purpose is, at what historical moment.” When historical data privileges its own systems of knowledge, it’s hard to trust the archives. It wasn’t till about 15 years into the book that I began finding alternative sources, inspiring my own “interventions.” A way perhaps to make fiction and an alternative record that I could trust.

I’ll give examples. The titular character, Nomi, is made up. Her brother Zee is based on a historical figure. The first shot fired on South Andaman Island during the war was by a boy trying to save a chicken from Japanese soldiers. This actual event frames the opening chapter. Zee is based on the boy, Priya on the chicken. I took the liberty of giving Zee and Priya a loving sister.

The jailer, Cillian, is also based on a historical figure. I found reference to him in male prisoner testimonials. He is particularly feared by Prisoner 218 D. After the surrender of the Japanese, when the British reoccupied the islands, part of their strategy involved enlisting the help of former jailers. Cillian returns, with all the horrors that he took part in buried, along with my prisoner’s name, beneath an official narrative of “white savior.”

Too, the knowledge that you speak of between human and nonhuman. It’s essential in all my books. For me, the physical world tells the emotional truth. One that’s displaced when human and nonhuman reciprocity is displaced. So, for instance, the cost of war on indigenous fishermen because of underwater mines that removed them from their oldest food source and ally, the sea.

I can’t say how I accessed these interiors. Love. Listening. A willingness to stay a long time, for instance, with the “knowing” of the winds that you mention. Interventions of knowing require immersion, empathy — these are acts of faith. There’s a scene in the book in which an old man bemoans that the British never took their shoes off before entering a temple. I took my shoes off many times, yet I wasn’t given permission to truly enter till I found Nomi.

“There is Freedom in Not Having a Script,” a conversation with Aracelis Girmay. Read it in The Los Angeles Review of Books.

2. Of course, the main thing about islands is that they are surrounded by water. While I was reading your novel, I kept getting the sensation of water. You evoke the sea, rivers and frequent cyclones on the islands. Indeed, early on in the novel, protagonist Nomi learns the names of several bodies of water:

The Arabian Sea. The Andaman Sea. The Bay of Bengal, which was not a sea but part of a sea. The Indian Ocean, with too many bays to name. The Pacific Ocean, around the corner. She recited these names again. Nomi was the keeper of seas that flowed into each other, into her bowl. Bodies of land, on the other hand, did not flow into each other, she could not collect them.

How did you go about writing about this littoral world?

It has helped to live on different islands. As a child, in the Philippines, Japan and Britain. As an adult, on Oahu, in Hawaii. I’ve lived in every place that plays a role in the book—Japan, England, even Hawaii—except the one that both my parents were born in, India.

But coming back to your question about the sensation of water, I’m glad it was ever-present for you. There’s something about being on an island that shifts how we experience time. For instance, Oahu is where Pearl Harbour is located, yet the monument seemed further away than my memories of Tokyo, where I’d apparently spoken a little Japanese (since forgotten). Like many South Asians, Japan for me was “haute Asia”—art, ceramics, fine cuisine. It was beauty and elegance, politeness and hospitality. I had happy memories of Tokyo, especially of a man who helped me to steal my first rose for my mother. The Japanese characters in my book, particularly the dentist-spy Susumu San and Dr. Mori, came to me in a flash. With Susumu San, I saw him riding a bicycle one day, and barely had to revise his sections. I have often wondered if he was a version of the man who helped me to steal the rose.

On Oahu, other images came close, including of my family resettling in Pakistan after leaving Japan and England. In Karachi, our house was near the sea. Though I couldn’t see it, I could smell the sea. I could feel the shifting winds (perhaps like my character Aye). This was during the Cold War, when the US fought the Soviets in Afghanistan through Pakistan. Though at one time Karachi had been a fishing village, the city that I grew up in, where I could hear and feel the sea, became a battleground. And the battle was happening on land, not water. Yet, while writing this book in Hawaii, I seemed to fly to an in-betweenness where borders are mapped by water. Possibly, this allowed me to find a language for characters who exist between empires and seas ...

A conversation with Claire Chambers. Read it in Full Stop magazine.

3. How do you define and understand the genre 'Historical Fiction'?

Alessandro Manzoni said historical novelists put 'flesh back on the skeleton that is history.' So that's one answer. But Manzoni was a white man, and history's skeleton and flesh have been constructed by privilege. My generation of women, the first to be born in Pakistan, has largely been severed from our history and geography, by the same forces that write the history and draw the maps. So I reject the notion that the history we're given is the only one there is. There are many histories, many ways to think about whose history we are meant to believe and meant to erase. For me, historical fiction is first and foremost deeply personal. It's a way to imagine the unimaginable. A way to embody stories not meant to exist.

"Imagining the Unimaginable With Historical Fiction," a conversation with Aarushi Agrawal. Read it in First Post.

4. The novel juxtaposes the brutality during the war with the enchanting beauty of the island. The island heaves with life in the novel. Did you consciously work on this?

One of the questions that haunted me from the start was that despite the coconut groves and crystal bays that the British found in this pocket of the Bay of Bengal, they turned it into a penal settlement. What is the mind that looks upon beauty and sees, instead, a means of torture? That wishes for whipping stands, gallows, and eventually a highly sophisticated panopticon prison? I was fairly preoccupied with these questions. They are closer than we want to acknowledge. We have always been attracted to beauty, and always attached it to power, with devastating consequences. So I am still haunted by these questions. What do we do with what draws us—preserve or spoil it?

"What the Body Remembers," a conversation with Shireen Quadri. Read it in Punch magazine.

5. Trauma returns to the victims in the novel … (yet) their personal experiences lead them to what may be called victim/survivor empowerment. As Joy Kogawa reminds us: “What is healing for a community is more than just a solution of a political kind. What heals is a process of empowerment.” How would you describe your characters in light of (this)?

The body doesn't forget the silence that accompanies each violence. In The Miraculous True History of Nomi Ali, Kaajal tells Prisoner 218D: ‘the opposite of peace is not war. The opposite of peace is inertia.’ Writing for me is a way to resist inertia ... Writing (is also) a deeply immersive act—it demands all of me, physically. Since I never have an outline or any kind of plan, the pen and page become the entire body. The physical world tells the emotional truth.

Which brings me to the necessary question of healing. One reader pointed out that though my characters carry trauma in their bodies, they also heal each other physically, with water and earth. (She noted: Haider Ali’s mother feeding him Multani mitti. Aye holding Zee when they swim. The aborigine women painting men with clay. And many other examples I didn’t consciously see.) I’d emphasize that what happens when the body is written out of history and memory, generation after generation, can only be written, reclaimed, and healed by the body. So I agree that a political solution is not enough. Healing requires more than that: it requires that the body be written back into history, story, and collective memory.

"From a Ruin of Empire," a conversation with Aroosa Kanwal. Read it in Southeast Review.

6. History is often told from a male gaze. How challenging was it to address these inequities in historical fiction?

At the start, it wasn’t challenging so much as frustrating. I encountered references to women in the freedom movement as either feminine ideals—dutiful and chaste sisters and wives who supported the efforts of men, mostly through social work—or else championed for being “as strong as men.” There the narrative stopped. The social and sexual stigma around their life in the prison colony meant that they were barely if ever mentioned in books written by men.

But at some point, I stopped caring about what had or had not been said. I entered that other world, the one of fiction, where the focus is on language and character. The unnamed political prisoner in my novel was the first character I wrote, over twenty-six years. My interest was, from the start, in her daily and interior life, as someone transported and imprisoned, more than in what she did to end up there. I didn’t want to erase or champion her: I wanted to know her as a person, in her entirety. She was a seed that I carried with me, across many seas. I just had to be patient, to let her speak. The same was true for Nomi, who in a sense becomes the keeper of her family’s history. I wanted to know how she got there. I wanted to value her life, as a young girl who grows up not only between two colonial powers, but between two parents who largely don’t see her. I just had to hold her, and listen, and forget about any other gaze.

“The Story Has To Come From Within,” a conversation with Ziya Us Salam. Read it in Frontline.

7. This novel I find to be your most history-conscious to date, on many levels. One is your sense of history and history-making, with emphasis on the question of who (gets to) write/record and hence define it. Also … this novel will likely find a place in the literature of the subcontinent’s history, as a record itself—because there is little by way of fiction on it. Could you tell me how you view your role as a writer here?

When I began, in the 1990s, I’d gone to the library to find a book. I found instead a book that referred to the Andaman Island “prisoner paradise.” I found the book I wanted to write. I had no idea how to start. I only knew that this was my history, not a separate Indian history. And I knew that I had not been taught it in Karachi.

I don’t know how I saw my role. I think there were a multitude of impulses I could not have identified—curiosity about what I’d discovered, rebellion against my own ignorance and the notion that the history I was given is the only one there is. I think I always rejected that notion. I have a healthy dose of scepticism. I ask a lot of questions. Mind you, I’m also dutiful: for the next twenty years, I collected every article and image I could find on the islands. But what sustained me was the fiction more than the facts, the license I gave myself to create. Which is to say, the license I gave myself to exist. At some point I did realize that no other fiction on the islands during the 1930s and 40s had been written before, at least, to my knowledge, in English. Now I’ve come to wonder whether it had to be written by someone in my position, someone severed from my history and geography by borders, without the privilege to suppose much, yet with the understanding that everything had to be learned and imagined from scratch. And if my novel comes to be a kind of record itself, I am honored.

A conversation with Pooja Pande. Read it in Café Dissensus.

8. Watch the recording of the virtual US launch of The Miraculous True History of Nomi Ali at City Lights Bookstore on April 18, 2022, in conversation with writer, educator, and editor Q. M. Zhang.

9. Watch the virtual launch of The Miraculous True History of Nomi Ali at the Islamabad Literature Festival 2020, in conversation with Dr. Munnaza Yaqub and Dr. Sonia Irum.

Bonus: Yaqub and Irum know my work intimately (its ‘environmental consciousness’). Check out Yaqub’s The Toxic Legacies of Colonialism on Nomi Ali; The Landscapes of Vertical Wilderness on Thinner Than Skin; and Yaqub & Irum’s joint paper on Trespassing & The Geometry of God.

10. Watch the virtual “Isolation Central” 2020. We discuss the quarantine, birds, and, of course, Nomi.

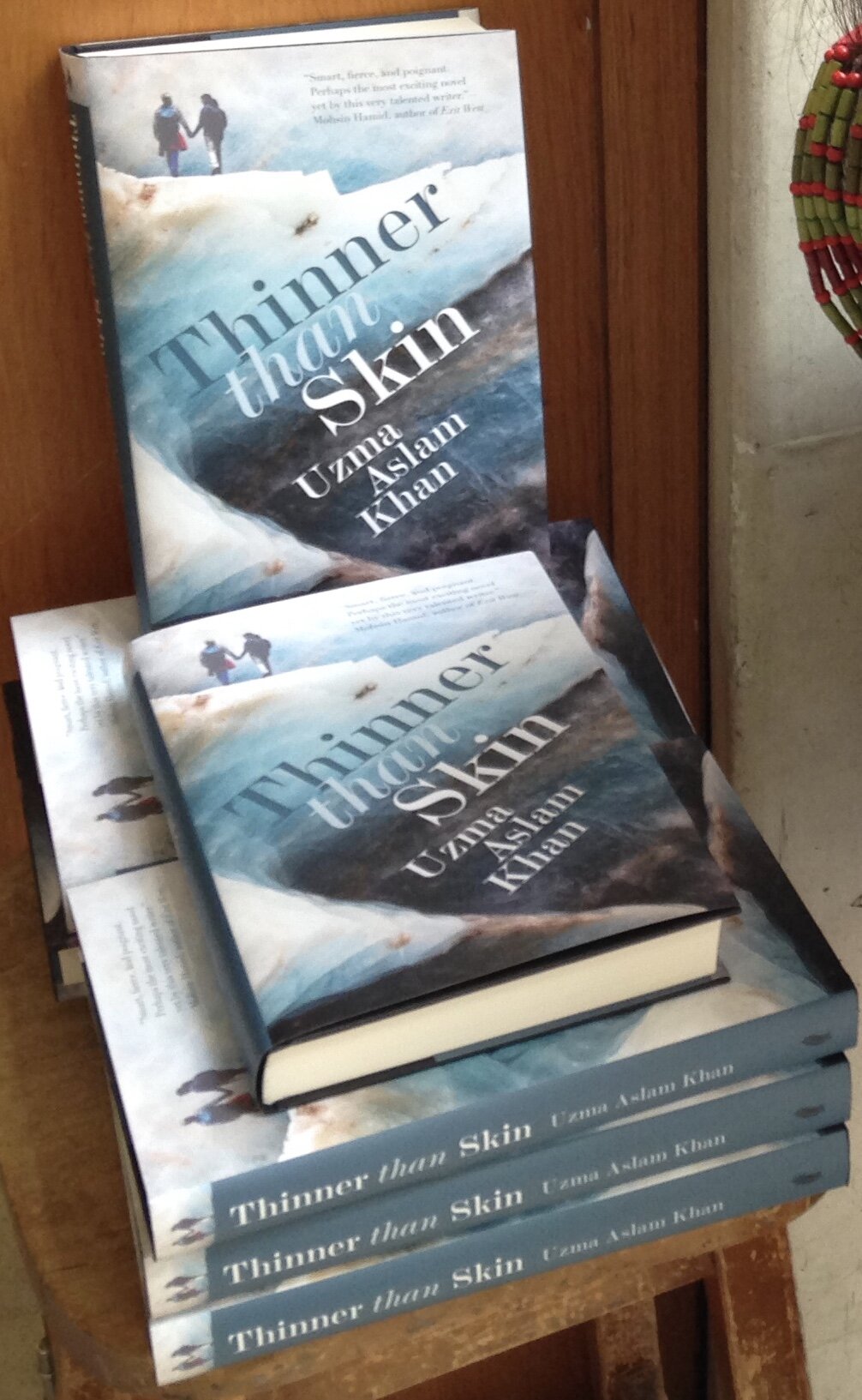

THINNER THAN SKIN

—Interview Highlights

Thinner than Skin could be a story about love and the search for identity. But it could as easily be a story about the impact of militancy on nomadic communities in northern Pakistan. How did you bring all this together?

I’ve never mapped out a novel. I don’t really trust maps, because the lines change as soon you find them. As if the form of a novel itself demands that you stay open to change, open to surprises. All my novels have begun either with an image and/or a voice. With Thinner than Skin, the spark was an Ansel Adams photograph of a waterfall. The force of the torrent inspired a line that has stayed in the book. All the threads of a novel, at least for me, come together through sensory cues, through acts of faith. There is no plan except to feel my way through it.

Read more of the interview in Dawn

I love how landscape is such a presence in your stories, like the Russian writers’ sense of how the land thwarts/shapes its people. Specifically in Thinner Than Skin, perhaps this has to do with how it explores transgression and guilt through Nadir and Farhana (and of course your references to Raskolnikov’s exile). What shaped such a visual perspective, this connection to land? It’s almost as if the ways of knowing each other, the world, god and ourselves are fused into a naturalist’s appreciation of our world and of our body … like in the detail of a flower, or in a glacier?

I love how you put this. I think I do have a naturalist’s love for our world … What shaped it? Perhaps my paternal grandmother’s open-to-the-sky courtyard in an old, crumbling house in Lahore that was filled with bats and ghoststs. Or it’s event older. My father’s nana was a well-known hakim of a small Punjabi town, and a year before my father’s death, he shared with me stories of his grandparents, how his nani would operate a chakki to grind wheat, while his nana prepared all the medicines for his clinic by mixing desi herbs that my father and his bothers would him collect. You know, even before he shared the memories with me, I had an image of those herbs and flowers, their colors and their scents.

‘I think a lot about inherited memory.’ Read it in The Hindu

3. A common thread in your books is the resourcefulness and sensuality of the female characters. Could you speak on this?

In Thinner Than Skin, Maryam is a semi-nomadic woman who comes from the Gujjar tribe. Yes, she has a rich spiritual and sensual life, but she keeps this from the public arena, in part for survival. The gap between the freedoms enjoyed in the public versus private spheres is one I’ve explored in my books, where women often occupy a different space that needs to be navigated, daily.

Read the rest in Star Turkey (in Turkish—the above is a translation)

4. Karachi: Watch the book launch and conversation at Karachi Literature Festival (2014).

5. Karachi: Hear my conversation on CityFM89 (2014).

6. Paris: Watch my interview with well-known bookseller, Libraire Mollat (2014).

7. San Francisco: Watch my talk at LitQuake LitCrawl; I read from “Ice, Mating,” a story in Granta that nests in Thinner Than Skin.

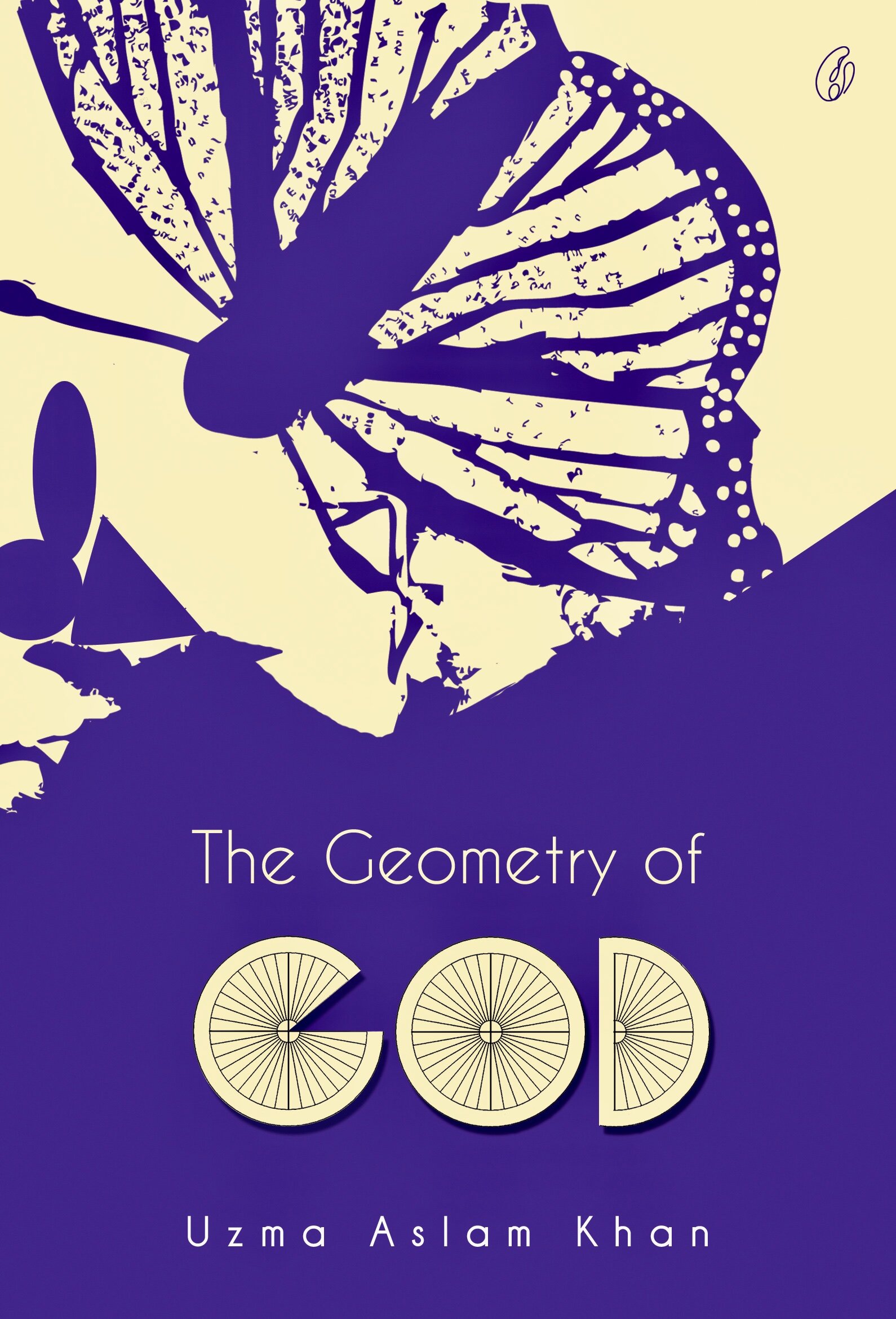

THE GEOMETRY OF GOD

—Interview Highlights

1. Can you say more about The Geometry of God?

My novel’s in part about a girl, Amal, who, while on a fossil dig in the Salt Range of the Punjab with her grandfather, accidentally makes an astonishing discovery about whales. On the same day, her baby sister Mehwish is blinded in an accident, and it falls on Amal to look after her. Amal grows up to become Pakistan’s only woman paleontologist, but is prevented, by country and family, from seeking the sort of knowledge that can fuel her infinite curiosity. But in teaching Mehwish how to ‘read’ with her fingertips, she helps Mehwish develop her own language in a way that allows Mehwish to negotiate the limits of the practical world that thrills and frustrates Amal. Enter Noman, who unwittingly sets in motion a chain of events ... But the book (is) also, by some miracle, the funniest thing I’ve ever written. Possibly because I wrote all three characters in the first person (my previous books are told by a third person narrator), the telling is intimate and playful.

Read the rest of my conversation with writer and editor Ahmede Hussain.

2. How has the cycle of violence (in Pakistan), and the tussle over who ‘owns’ the state affected you personally? Do writers have a responsibility to respond to what is going on around them—to protest, or record things for the future?

It affects me personally every day. But I’ll give just one example. I wanted to set (The Geometry of God) in the mountains. But my mobility was restricted, for many reasons. The fossil-rich land is owned by the army and I don’t come from a military or feudal or political family that can contact VIPs and get their daughter special favors ... Pakistan belongs to the army before it belongs to civilians, it belongs to men before it belongs to women, it belongs to women only if they are daughters of so-and-so and wives of so-and-so.

(To your second question) Writers have a responsibility to their work. How this responsibility is interpreted is really a very personal choice. Speaking only for myself, the hunger to know my place in the chaotic layers into which I was born helped make me a writer. It’s the hunger to make up for what was never said, and may never be said.

‘My Novels Focus On What Is Not Being Said In The News.’ Read it in DNA

3. In the years since you wrote The Geometry of God, the country has seen some of the most gruesome attacks on religious minorities, including inhumane abuses of the blasphemy law. What is your perspective on this?

When The Geometry of God was completed in 2007, there were many documented cases of blasphemy charges being levelled against innocent civilians, particularly Ahmadis and Christians. My character Nana was not based directly on any one person, but I read (about) ridiculous spelling errors, word shuffling, rumor, and revisionism, all of which I draw on in the book. And then last year it happened again: a Christian eighth-grader was accused of blasphemy for a spelling error in a poem. For a Pakistani writer, life imitates art all the time.

‘If This Were A Civilized Land, Faith Would Be Private.’ Read it in New Age Islam

4. Check out Reading Guide Questions for The Geometry of God in Oprah magazine

5. Check out my conversation on “The National Language” in Granta

6. If you didn’t earlier, watch my talk at LitQuake LitCrawl San Francisco 2010, in which I disclose writing The Geometry of God on tissues.

TRESPASSING

—Interview Highlights

Can you talk a little about the process of building your stories? And about the process of building yourself as a writer?

My books usually begin with a setting, and an image or a voice that roots me to it. In Trespassing that image was Daanish’s drive home from the Karachi airport, about thirty pages into the novel. That’s the first scene I wrote, and then, very slowly, I built around it, like a caterpillar, linking threads. I rely on research to some extent, too. With Trespassing, my research included keeping silkworms, which I could then observe close up, and also visits to bus body making workshops both in Karachi and in Lahore. But the majority of the information I collected wasn’t even needed to tell the story, because the process is mostly sensory and unconscious.

How I built myself as a writer is hard to say, since I didn’t consciously try to be a writer. Rather, writing is something I have always done, ever since I was a child, and at first in great secret. But I can share with you some pivotal moments that likely kept developing the writer in me. At the age of seven, for instance, I wrote a story about a princess and her horse that won me a copy of Oscar Wilde’s Fairy Tales, and this must have encouraged me. I have Wilde’s book with me still. I was living in London at the time and a lot of English girls were taking riding lessons, but my family couldn’t afford to. Perhaps I wrote the story both for pleasure and as a way to make up for some absence. And I wonder if these continued to be motivating factors as we moved back to Karachi from London in 1979.

Read the rest in Bookaholic Romania (in English)

2. How did Salaamat evolve? The character and the descriptions of the underworld, the bus “addas” etc. were really well done. Did you research this?

I don’t know where Salaamat came from. With a few of the characters—like Daanish and Dia—there are superficial parallels that might be drawn to my life. (Like me, Daanish was in the US during the Gulf War, and I too washed dishes to put myself through college, and Dia is a woman who grew up in Karachi during the chaotic 1980s.) With Salaamat, there are none. And yet, he is the one who came to me the most easily. His sections I revised the least—maybe just a sentence here or there. I knew him right from the start. And this is a little frightening, as his parts are the most violent. It must be true what they say: there is violence in all of us.

To capture his art, I made visits to bus body making workshops in Karachi and Lahore. I couldn’t have written those scenes without observing bus and truck art firsthand.

Read the rest in Telerama France (in French)

3. Also check out my profile in The Independent, for the book’s UK launch in 2003. Excerpt:

‘The effect of constant uprootings on (Khan’s) imaginative life seems clear. Trespassing, her second novel but the first to be published here, is set in Karachi, where Khan spent her own formative years. It follows two lovers, Dia and Daanish, through an increasingly desperate battle to sustain their feelings for each other in the face of mounting pressures from family, friends, society and circumstance. But Khan's novel is far from soft-centred romance. The young couple's alternating narratives are interleaved with other voices offering stories of cultural alienation and political violence. The atmosphere of threat is drawn from Khan's own experience ... Trespassing was completed several months before the events of September 2001. Its focus on the first Gulf War, and on previous Afghan conflicts, leaves her unsettled by her own unwitting prescience. But then, as she puts it, "so much of this book is about history coming back to haunt you."’